Cam McRae

from issue 28-1

Two boats loaded with skeptical journalists and piloted by veteran test boat drivers paused in the brackish waters of Virginia’s Chuckatuck Creek. Side by side, at a hand signal, they launched out of the hole in a classic drag race. Although seemingly equal for a split second, one of the boats quickly established its dominance, leaving its rival behind, leading by four boat lengths in three hundred yards.

The boats, Formula 260 bowriders, had been carefully matched by the expert crew at Volvo Penta’s Marine Products Test Center. Weights and centers of gravity had been equalized.

Both were powered by 380 horsepower V8s actuating dual propeller outdrives. Nevertheless, the winner was a second quicker to 20 mph, 1.5 seconds quicker to 30 and more than two and a half seconds ahead at top speed. The slower boat was equipped with MerCruiser’s big block 8.2 MAG. The swifter craft featured Volvo Penta’s all-new small block six litre V8-380-CE.

I have no doubt that the boats were equal. The test engineers had tried every combination, swapping the engines boat to boat and attempting the same test with the equivalent Volvo 8.1.

The Merc was fresh, well maintained and the crew had evaluated numerous prop selections for the Bravo III, honing its performance in the same manner as the Volvo package.

To get at the story behind the story, we have to rewind to the fall of 2009. GM Powertrain sent the marine power world reeling with the announcement that they would cease production of the beloved 8.1 litre big block V8 in January 2010. As a replacement, both Volvo Penta and Mercury Marine evaluated the then current GM 6.0, particularly the supercharged version. The blown 6.0 showed promise, producing excellent performance numbers in marine trim. Ultimately it was rejected, both firms citing high initial cost, difficult service procedures and the potential that any serious failure would be enormously expensive for the consumer.

MerCruiser came up with a very creative solution. Recognizing that Mercury Racing sourced most of the internal components and the heads for their competition big block engines from the aftermarket, they arranged to obtain all those bits on a production basis and then cast their own block. Voila! An all-MerCruiser 8.2 litre V8.

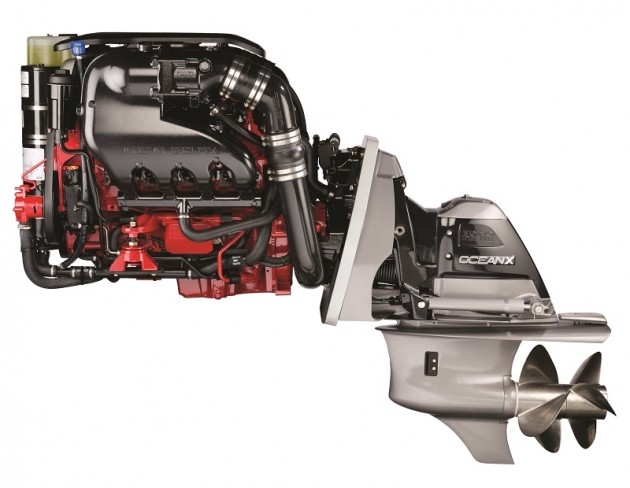

Volvo Penta took a wait-and-see approach. Betting on the future availability of an appropriate powerplant, the company stockpiled the 8.1. Their faith was rewarded. Following the near-collapse of the auto industry, a revitalized General Motors re-launched a serious effort into the creation of a powerful, highly efficient and environmentally responsible light truck engine. The result was a fourth generation (Gen-IV) small block dubbed the L96. Volvo Penta purchases the L96 from GM Powertrain off the shelf, with no internal modifications required for marine service.

Other than its basic architecture, this 364 cubic inch engine bears little resemblance to the 265 V8 that first appeared in the 1955 Chevy. From its state of the art multiport fuel injection to the massive girdle that supports the crankshaft bearings, this is a small block for the 21st century. But the one single feature that defines the L96 as a superlative marine engine is variable valve timing or VVT.

Under control of the ECM computer, oil pressure is used to advance or retard the cam timing relative to the crankshaft’s rotation. Simply put, if the cam is advanced, the torque peak is moved down the rpm range. When it is retarded, power moves toward the upper rpm.

Our boats operate in essentially two states, either accelerating and struggling to break free of the water’s heavy restriction, or planing freely and at speed. With VVT we have two engines in one. A torque-y gruntmotor to get us up on plane – that smoothly morphs into to a top end speedster.

VVT isn’t the only contributor to the 380’s startling performance. The ECM keeps the engine in perfect tune at every point in the rev range. Ignition timing is constantly optimized and feedback from pre and post O2 sensors on the catalytic convertors is used to maintain an ideal air/fuel mixture. Fuel economy is improved by 12% over the 8.1 and emissions levels handily exceed EPA/CARB requirements for the foreseeable future. For example, the 380’s virtually odour-free exhaust contains only about 35% of the emissions of a non-catalyzed 8.1. At idle, carbon monoxide is reduced by 95 %!

Weight is always an issue. Although Volvo couldn’t do much with the basic L96, every part added to marinize the engine has been engineered for dependability – and light weight. The exhaust manifolds are aluminum and all the bracketry is either alloy or space-age composite. Installed, Volvo’s V8-380-CE package scaled in at 305 pounds less than the MerCruiser.

With lessons learned from the 8.1, GM designed the L96 for easy serviceability. Volvo added their own touch, locating the major service points to the top and front of the engine.

Not surprisingly, the International Boatbuilders Exhibition (the world’s biggest tech oriented marine trade show) took all of the V8-380’s merits into consideration – and rewarded the new engine with its prestigious IBEX Innovation Award for 2012. Well deserved.

There was another, smaller boat on the Test Center’s docks that week. Whereas the Formula 260s involved maximum power, the Monterey 228’s engine proved brilliant by making less. The story behind this part of the story began when Volvo was seeking a replacement for the 4.3l V6 engine being dropped from their line up. Many smaller new boats are rated below the 250-300 hp typical of today’s 5.7 litre V8. Acknowledging that their 5.7 was only about 7 inches longer than the old V6, slightly narrower with the cat-equipped exhaust manifolds and only 60 pounds heavier, the engineers de-tuned a 5.7.

Primarily by limiting the throttle body opening, they restricted the engine’s output to 225. And made a discovery. With the intake body never quite at WOT, three phenomena occurred. First, the air in the duct gained and maintained velocity. That, in turn, provided a strong intake signal for the ECM’s tuning calculations. And, as a happy byproduct, the intake’s roar was considerably reduced. As on the 380, the 225’s ECM is able to tune the fuel mixture and ignition timing in constant harmony with the engine’s needs – which results in the most responsive and flexible Chevy 5.7 I’ve ever throttled. It’s also the cleanest engine ever offered by Volvo, even outpointing the 380.

As you might expect, acceleration is brisk. But, where this V8 really shone was in the mid-range, around that 30 mph sweet spot where we all spend so much time. The Monterey 228 is an easy-running boat, requiring little to keep it going once up on plane. So, I trimmed the drive in, jamming the bow down and forcing the engine to earn its wages. Even under those unnatural, but challenging conditions, the 225’s throttle response was both instant and fluid, always keeping pace with my input.

I’m guessing, but based on the Monterey, it would be reasonable to predict that the 225’s performance numbers would be comparable, perhaps marginally slower than a typical 300hp 5.7. That is, until top speed where the 300 would likely outpace it by 4-6 mph. I’d give up that top speed for the 225’s flexible power, industry-leading emissions numbers and unprecedented fuel economy. For those who must have the shotgun holeshot and 56 mph top speed of a 300, maybe they could ask Volvo Penta to detune a 380!